With Jerome Powell indicating at the Jackson Hole Conference that tapering could begin this year itself, the phrase 'taper tantrum' has made a comeback to the lexicon of economics journalists. Notably, the minutes released from the July gathering of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) also point towards the same direction.

Through this post, we seek to understand what the taper tantrum is and its implications. We also look at some insights from the 2013 experience.

To begin with, tapering is the gradual reduction in the number of large-scale assets purchases by the Federal Reserve. These asset purchase programmes are usually put in place during an economic crisis and then need to be gradually done away with, once the normalcy restores. And when this doing away happens, there are some ramifications. One of them is the taper tantrum.

Taper tantrum describes the increase in bond yields of the US Treasury that happened in 2013 post the announcement by the Fed about future tapering of the Quantitative Easing policy. Given the interlinked nature of the global financial markets, this did affect countries other than the US too. But to understand its actual implications we first take a look at the policy of Quantitative Easing.

Quantitative Easing, Its Role & the Pandemic

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a monetary policy under which the central bank buys long-term securities from the market to increase liquidity and boost lending and investment. Similar to Open Market Operations, QE is usually deployed when the nominal interest target approaches zero. The process is as follows:

When a central bank intends to buy securities, they create a cash reserve on the liabilities side of their balance sheet for the same.

This money that was essentially created out of thin air is then used to purchase the said securities.

As the bank goes ahead and purchases more and more securities, the money goes into the hands of various financial institutions.

These financial institutions now have higher cash at their disposal that they can lend, hold, or spend as per their discretion.

This excess supply of liquidity in the market causes the interest rates to fall making it cheaper and easier for individuals and companies to borrow.

Furthermore, the buying up of securities causes bond prices to increase. An increase in the bond prices leads to a fall in the bond yields which in turn causes a fall in the interest rates.

All this makes it cheaper for businesses and consumers to borrow and fuel the economy, thus improving the economic situation.

Major Central Banks across the globe undertook the policy of quantitative easing during the Global Financial Crisis and then again as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In March last year, the Federal Reserve announced a quantitative easing plan which consisted of securities purchases of over $700 billion. Later in June, the Fed said that it would purchase large-scale bonds worth at least $120 billion each month until further notice. The goal was to beat the pandemic woes and boost economic recovery.

Risks & Limitations of Quantitative Easing

QE boosts the economy, so a question must arise that why can't we keep the policy going forever. I would like to point out three key reasons1:

Possibility of Inflation

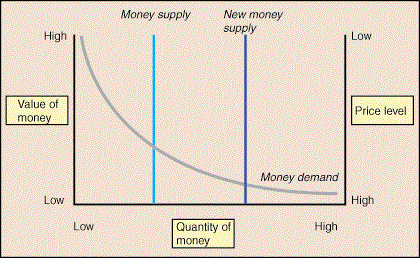

According to the Quantity Theory of Money, the general price level in the economy is directly proportional to the amount of money supply. The value of money decreases as the amount of money in circulation increases. So, when policies like QE get implemented, there is a risk of creating high inflation.

Now an important factor to note here is the policy lag, i.e. the timeframe between implementing a policy and its results showing up. The increase in money circulation can create inflationary pressure in the economy that may show up too soon or too late which leads to uncertainty. A high delay can cause the situation to get out of hand before policymakers identify it and spur to action. Critics argue that this can lead to runaway inflation.

It needs to be noted that if the production grows along with the money supply in the economy, there wouldn't be any risk of inflation. The value of money will likely remain the same in that case. In fact, if the production outpaces the increase in money supply, the value of money could indeed rise despite the monetary growth. All this, however, needs to factor in the time-lags in macroeconomic variables which makes it difficult to keep track of the situation.

Lending Choices by Financial Institutions

The money supply created by the central bank does not directly go into the hands of the consumers and businesses. Instead, as discussed earlier, it goes into the hands of financial institutions. Now, it's up to those institutions whether they wish to lend it out or not. They might choose to simply keep it on their balance sheet instead of lending it out. If there is a high level of such reluctance in the economy, QE will fail to stimulate the demand.

On the other hand, financial institutions can also opt to lend out freely to firms and individuals instead of shoring it up on their balance sheets. This increase in credit availability definitely helps out in the economic revival, however, it has a negative aspect as well that we discuss in the next point.

Excessive Borrowing & Zombie Firms

The artificially low interest rate created by QE invites companies to borrow more and more. Some of these borrowing firms do not have enough profits to service their debts over the coming years. The result is the formation of zombie firms. Zombie firms slow down the economic growth and are often regarded as a cause for Japan's Lost Decade.

According to a report titled "The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences" published in the BIS Quarterly Review of September 2018, the presence of zombie firms lowers investment in and employment at productive firms. The publication uses firm-level data on listed firms in 14 advanced economies and documents an increase in the prevalence of zombies since the late 1980s. Their research notes that this increase is linked to the reduced financial pressure which in part reflects the effects of lower interest rates.

Quoting from the conclusions of the publication,

Lower rates boost aggregate demand and raise employment and investment in the short run. But the higher prevalence of zombies they leave behind misallocate resources and weigh on productivity growth. Should this effect be strong enough to reduce growth, it could even depress interest rates further. Our study cannot answer this question. We leave the exploration of this trade-off to future research.

This clearly shows the risks associated with lower rates and the thus created zombie firms. Here is an article that analyses the issue of zombie firms in further detail.

Taper Tantrum of 2013

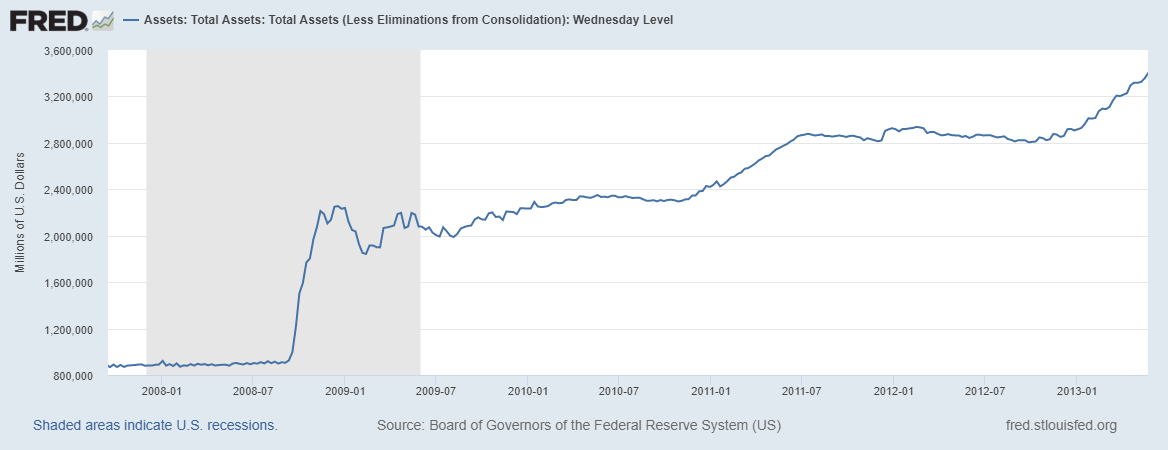

After the fall of Lehman Brothers and the subsequent crisis in 2007, the Federal Reserve started a massive bond purchase program. The result was the assets on the Fed's balance sheet tripling to almost $3 trillion in 2013 from $1 trillion before the crisis. The graph below illustrates the same:

In 2013, the economy enjoyed a largely positive outlook. In May that year, Mr Bernanke (the then Chairman of the Fed) speaking before the Congress said that the Fed could begin tapering the bond purchases soon, provided the positive economic outlook continues. The market reacted with the bonds market crashing as investors sold off the US Treasuries and the stock market temporarily pulled back.

This announcement had a much larger effect on the emerging markets. The graph below by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas plots the exchange rate of a set of 13 large emerging-market countries w.r.t the USD. It is weighted by GDP and tracks the changes post the May 2013 announcement.

The emerging-market rates fell by 6% within four months in the aftermath of the announcement.

This was the Taper Tantrum.

How Was India Affected

As the investors dumped the US Treasury Bills fearing the selloff by the Fed, the Treasury Yields rose sharply. This led to an outflow of funds from the emerging markets. Importantly, India was put on the list of 'The Fragile Five' by Morgan Stanley that year.

As the Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) pulled out their investments from India, the Rupee depreciated by over 15% between May 22 and August 30, 2013. The investors were wary of investing in India because of the sluggish growth and when the Rupee fell, they started pulling back their investments. This led to a further fall in the value of the Rupee and thus led to a vicious cycle.

Meanwhile, the RBI sprung into action. RBI raised the interest rates and began selling US Dollars to stabilize the fall in the Rupee. But given the needs of the Current Account Deficit, it couldn't sell enough. In July, the RBI raised the bank rates from 8.25% to 10.25%. In August, the RBI announced the sale of bonds worth Rs. 22,000 Crores each Monday to soak out the liquidity of the Rupee in the market. A special window was opened up for forex swaps with the state-owned oil cos. The gold imports were tightened as well.

At one point, the Rupee had depreciated by 18%. The press indicated that India might be heading towards a financial crisis. This warrants the question that why was India so vulnerable.

Why Was India So Vulnerable?

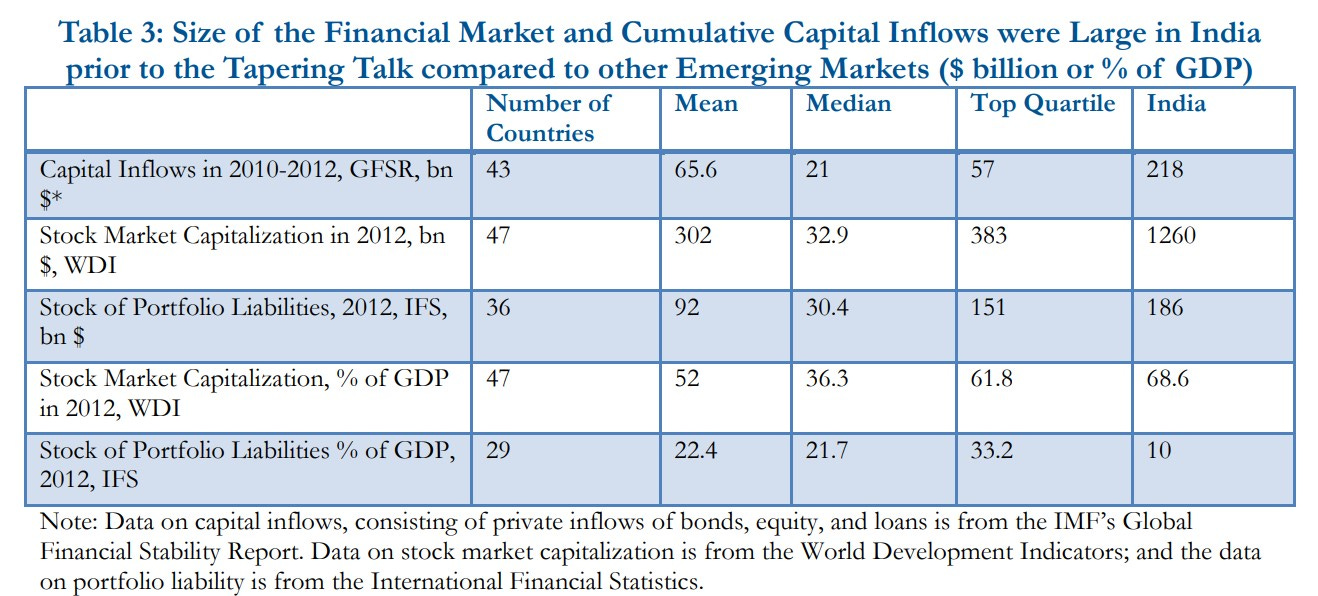

A World Bank policy research working paper authored by Kaushika Basu, Barry Eichengreen and Poonam Gupta gives two reasons for the adverse impact on India:

The large capital flows in prior years and the large and liquid financial markets made it a convenient target for investors seeking to rebalance away from emerging markets.

The macroeconomic imbalances in India made it vulnerable to capital outflows and limited the policy room for manoeuvre.

I am not elaborating much from the paper but it is definitely worth a read. The authors have provided a detailed analysis of the impact of the taper tantrum on India. They also look at the policies adopted by the government at that time and put forward a medium-term policy framework.

Taper Tantrum v2021?

As discussed earlier, central banks across the globe have undertaken monetary policies to fence off the pandemic woes and boost economic recovery. Last June, the Fed announced the purchase of large-scale bonds worth at least $120 billion each month until further notice. The Fed balance sheet has now ballooned to more than $8 trillion:

Last month, Jerome Powell - the Chairman of the Federal Reserve indicated that the tapering could begin this year itself. He also added that the interest rates are likely to remain low for a while because there is still much ground to cover to maximise employment.

A former Fed official recently said that the tapering of asset purchases could begin in November itself, provided the economic outlook stays positive.

So, we can clearly conclude that the tapering off of the COVID-19 induced quantitative easing is in sight during the near future. Contrary to what we saw in 2013, the markets as of now have exhibited no substantial negative reaction to the prospective tapering yet. It seems like there wouldn't be an iteration of the taper tantrum this time. Does that mean India stands risk-free?

Where Does India Stand this Time

India's forex reserves reached a record high of $642.453 billion in the week ended September 3, 2021. Given the high forex reserve, we can conclude that the central bank would be able to step in and mitigate the situation if required.

Meanwhile, the Current Account Deficit ended in the positive territory during the last fiscal year with a surplus of 0.9% of GDP. The Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) by the RBI expects a deficit of 0.8% of GDP (at market price) in 2021-22. This is better than the deficit of 1.7% of GDP that was seen in 2013-14.

Hence, we can see that India's external position is clearly better than the one in 2013. There is a lower Current Account Deficit along with a larger forex reserve.

A report published by CRISIL notes similar observations. However, the report also notes that the domestic macros of India remain weak, though recovering. The GDP is moving towards the pre-pandemic levels, but the pace is slower as compared to other emerging markets. And there is also a high level of inflation along with high government debt. Here is a snapshot from the report highlighting the key vulnerabilities:

Looking at the stance of the government, we see that the Chief Economic Advisor of India recently said that India is ready to face the ripple effects (if any) of the Fed taper this time. Unlike the post-GFC scenario of 2013, India is in a much stronger position now. The industry experts also seem to agree with the opinion. We had IDFC AMC's Suyash Chaudhary say that India may escape the brunt of a paper tantrum.

How well the actual scenario pans out, only time will tell.

I hope that this rather long post was worth your time to go through. Unlike the last post where I appended some interesting links after the main content, this time I have added them within the post itself. Do go through them if you’re interested to learn more about the topic.

Feel free to reply to this newsletter or comment on the post to share what you think about the topic or the post itself.

I discussed only three risks associated with quantitative easing, however, there are several other risks including the creation of asset bubbles, inflation of the stock market prices, increased inequalities as well. These weren’t talked about because the content was limited by the number of words that can be used.

Good work Sagar, keep it up! 😅 It was highly informative!

Great article! 🥳